Error Handling in Rust, Part 1: Basic Idea

The approach Rust takes to error handling was one of the features that drew me in when I first came into contact with the language. Up until then, I worked in C++ and C# and codebases that used exceptions and I almost couldn't picture a different strategy. I was puzzled I hadn't seen these methods before. It only later struck me that the ideas pushed by Rust were not completely new, but improved on techniques that had been around for ages in some languages.

This post is the first part of a series focused on error handling in Rust. In this installment I go over the basics and mainly discuss the philoshopy closing off with comparison to exceptions in C#.

Simple Example

To give a simple example of how error handling works in Rust, let's consider a structure representing a coffee machine:

For this coffee machine an associated function is defined that is used to make espresso.

From the code, it is immediately apparent that the function may or may not yield the desired

product - an instance of a structure called Espresso. We see that the return value is

of type Result<Espresso, String> indicating that sometimes we may get a String as an error

instead. This will happen if the CoffeeMachine has less than 25.0 ml of water in the tank, or

if there is less than 7.0 g of beans in the hopper. Notice how the desired Espresso value and

the String error value are wrapped in Ok and Err respectively. We will see why in a few.

Elements of how errors can be dealt with by the caller can be seen in the following test

for the make_espresso function:

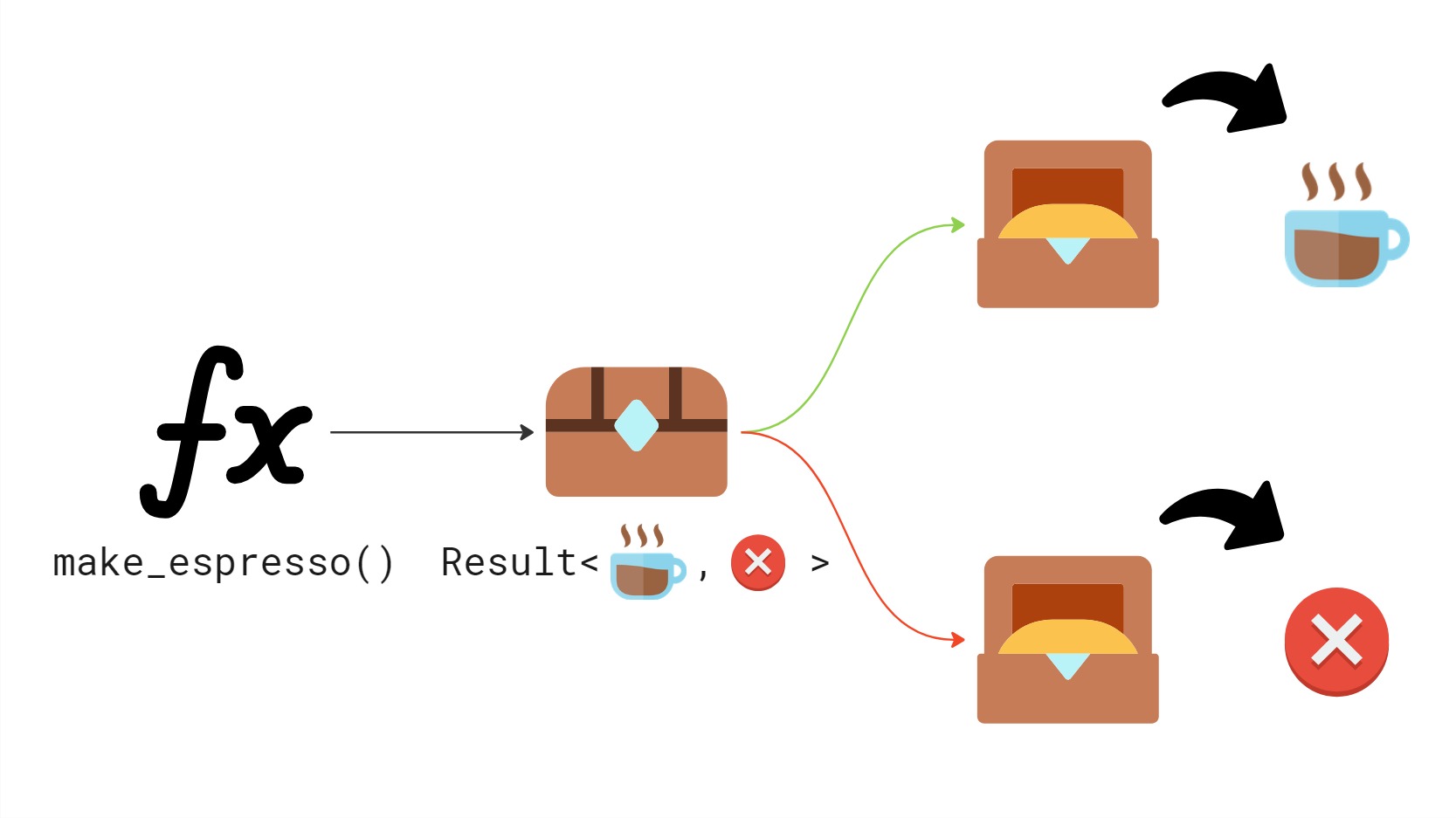

Notice how the returned value must be checked to determine if it's the desired type or an error. The following illustration simplifies the view of how errors are handled in Rust through an analogy:

Result is like a box returned to the caller. The box may contain either the desired return value

or an error value. We must inspect the box to find out which one we got.

Philosophy

The idea of making space for error information in the return value of a function is not new. Consider this C snippet:

int

Given that a file called non_existent does not exist in the working directory, executing this

program produces the following output:

fopen() failed: No such file or directory

The literal value NULL is reserved in the type FILE * by this function to indicate that it

was not successful. The value representing errors coexists with all possible valid return values

within the same type. Note also how the perror function is used to print the error extending

the message in its argument with more information about the cause.

Rust's Unique Take

Rust makes the implementation of the above idea very easy and makes the coexistence of values

for error signalling with desired outputs explicit in the declaration of the standard Result

type:

Note that the type is generic and that any two types can be passed as the type parameters T and E.

In the language, it's standard practice to return values of this type from functions that may fail. Here is

how a snippet of code analogous to the one seen in the previous section could look like in Rust:

The output is also almost the same, but note how the information about the cause is obtained

by directly printing the value carried by the error variant of the Result:

open() failed: The system cannot find the file specified. (os error 2)

The Trouble with Exceptions (in C#)

Here is how a function for opening files is declared in C#:

public static System.IO.FileStream ;

How can I see if and how this function might fail? I have to read the documentation:

(...)

ArgumentNullException

path is null.

PathTooLongException

The specified path, file name, or both exceed the system-defined maximum length.

(...)

Rust on the other hand is explicit. I can see the possiblity of failure immediately from how the function is declared in the code:

;

Another problematic aspect of exceptions is their propagation in the call stack. It has not only the potential to alter control flow, but also to terminate the whole program if not caught anywhere. I am sure most programmers who dealt with exceptions saw outputs similar to the following:

>dotnet run

Unhandled exception. System.IO.FileNotFoundException: Could not find file 'non_existent'.

(...)

For something not visible in the code, it seems that there is a lot of harmful potential in exception-based error mechanisms.

Furthermore, in languages like C#, error handling feels

opt in. You need to write a try-catch block to start handling errors. In Rust however,

the compiler warns about unused result types

making error handling an opt-out pattern (provided you care about warnings). This subtle difference

results in safer code in my opinion. Although it is possible to willingly sidestep these

safety rails, it must be a willing action of the programmer.

Summary

- Using

Result<T, E>as the return type of a fallible function is standard practice in Rust. Resultis like a box that may or may not contain the desired resultt.- The idea of making space for error information in the return value of a function is not new.

- Rust has greatly improved on the idea.

- We compared errors to C# exceptions which:

- are not visible in the code and feel implicit

- exception handling seems opt-in even though an uncaught exception can crash the whole program

- Errors

- are visible and explicit

- Handling errors is opt-out, the programmer must willingly disregard errors